The good news is there is no evidence that COVID-19 can be transmitted through food as a medium. However, other viruses such as norovirus and hepatitis have been noted for their involvement in foodborne infections.

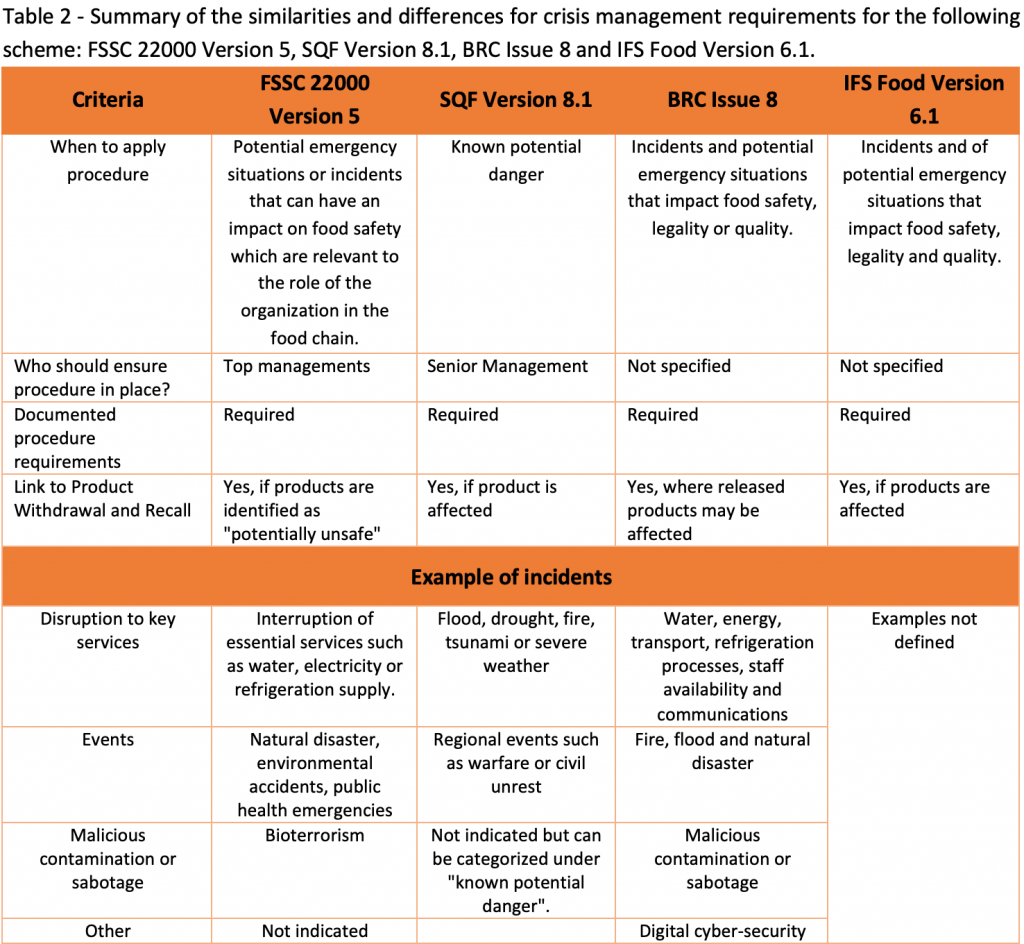

The spread of COVID-19 around the world have highlighted the importance for the food industry to have a contingency plan and/or plans to address emergency situations. Although we are in the midst of COVID-19, Crisis Management Planning still is a valuable tool for reference to handle future communicable disease outbreaks.

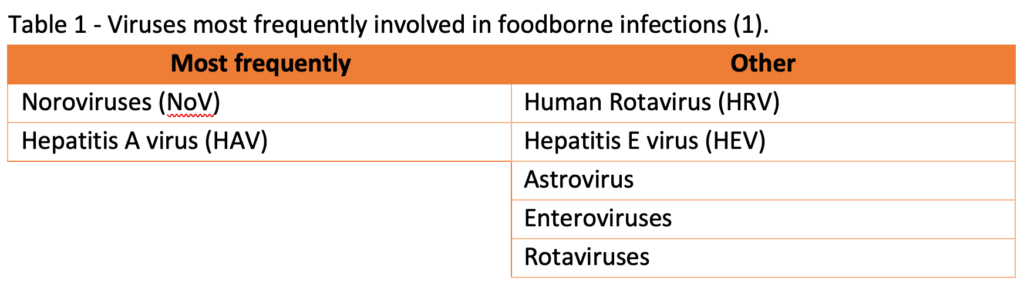

The good news is there is no evidence that COVID-19 can be transmitted through food as a medium. However, other viruses such as norovirus and hepatitis have been noted for their involvement in foodborne infections. Table 1 indicated the common foodborne viruses which are known to cause foodborne infections.